George Martin has been called the greatest producer in the history of music, but in addition to his undeniable contribution to record production and arranging, he was also a fine composer in his own right.

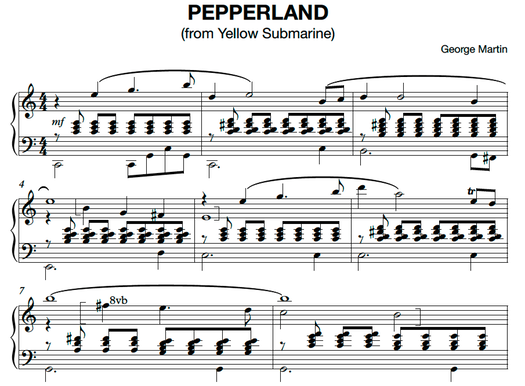

Some early releases by him as a bandleader are the inventive arrangements of Beatles compositions released on the albums Off The Beatle Track and A Hard Day’s Night. His facility for adapting existing material in creative ways would serve him well on the score to The Family Way (1966), which mostly consists of variations on the themes Love In The Open Air and The Family Way, composed by Paul McCartney. A similar situation arose on the 1968 soundtrack to the animated film Yellow Submarine, but in addition to the bouncy re-arrangements of the title song, he also composed a striking original dramatic score, featuring the balletic Pepperland theme.

(As a teenager I was the only person I was aware of who was excited about getting the orchestral score on Side Two of the Yellow Submarine album as much as more Beatles songs.)

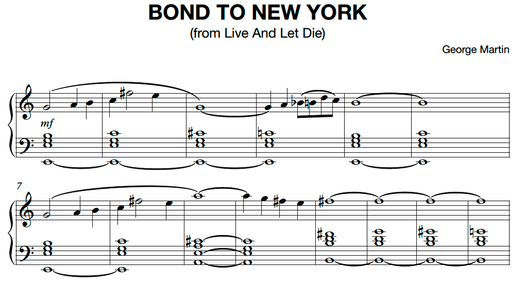

Circumstances reinvented themselves once again with the score to the James Bond film Live And Let Die in 1973, where Martin once again was able to weave motifs from Paul McCartney’s title song throughout the score with his own themes (as well as referencing material from John Barry’s arrangement of the original James Bond Theme), particularly his striking original theme for James Bond which appears throughout the score. With its wide range and alternating stepwise motion and melodic leaps, it is able to be equally exciting, atmospheric and romantic when necessary, through his sensitive arrangements and masterly spotting.

In Live And Let Die, George Martin’s orchestral sensibilities are maintained whilst completely updating the rhythmic foundation of the score from the 1960’s swing of much of his earlier work to that of a funk driven groove throughout, which befit the new era of Bond as well as the change of setting from Europe to New York. It is a masterwork of synthesising many differening dramatic and musical elements perfectly.

It’s also noteworthy that in the exciting Sacrifice music which appears in the opening and climactic sections of the film, one can also hear a technique originally deployed at the conclusion of the Beatles recording of A Day In The Life:

"What I did there was to write, at the beginning of the twenty-four bars, the lowest possible note for each of the instruments in the orchestra. At the end of the twenty-four bars, I wrote the highest note each instrument could reach that was near a chord of E major. Then I put a squiggly line right through the twenty-four bars, with reference points to tell them roughly what note they should have reached during each bar. The musicians also had instructions to slide as gracefully as possible between one note and the next. In the case of the stringed instruments, that was a matter of sliding their fingers up the strings. With keyed instruments, like clarinet and oboe, they obviously had to move their fingers from key to key as they went up, but they were asked to 'lip' the changes as much as possible too.

I marked the music 'pianissimo' at the beginning and 'fortissimo' at the end. Everyone was to start as quietly as possible, almost inaudibly, and end in a (metaphorically) lung-bursting tumult. And in addition to this extraordinary of musical gymnastics, I told them that they were to disobey the most fundamental rule of the orchestra. They were not to listen to their neighbours.

A well-schooled orchestra plays, ideally, like one man, following the leader. I emphasised that this was exactly what they must not do. I told them 'I want everyone to be individual. It's every man for himself. Don't listen to the fellow next to you. If he's a third away from you, and you think he's going too fast, let him go. Just do your own slide up, your own way.' Needless to say, they were amazed. They had certainly never been told that before."

(from "ALL YOU NEED IS EARS"- George Martin, originially published 1979)

(full orchestral gliss occurs at 1:36 mark and lasts til 2:09)

Cues appear as tracks "Gunbarrel And Snakebit" and "Sacrifice" on original soundtrack to Live And Let Die.

Though record production would always be his main focus, he continued to write effective and unique scores (particularly in the 1960’s and early 1970’s), including the whimsical underscore to Pulp (Mike Hodges, 1972) starring Michael Caine, and the touching music to the underrated Peter Sellers film The Optimists Of Nine Elms (Anthony Simmons, 1973).

In addition, his compositions can be heard in his fanfare for swinging London ‘Theme One,’ originally for Radio One, and ‘By George-It’s David Frost’, for David Frost’s Frost On Friday.

George Martin's often overlooked abilities as a dramatic and melodic orchestral composer were unquestionable, as demonstrated in the many different genres and styles he wrote for. Had he decided to devote himself fully to composition instead of production, I'm sure he would have similarly distinguished himself.