I have always been a fan of classic horror film (and scores).

One of my favourites is THEATRE OF BLOOD, starring Vincent Price, Diana RIgg, Ian Hendry, Arthur Lowe, Eric Sykes (and many, many more fine actors).

The film features an outstanding score by Michael J. Lewis. I had the opportunity to speak with him at length about the score and the creative process in general.

My sincere thanks to Michael J. Lewis for his generosity in taking the time to explore Theatre Of Blood.

THEATRE OF BLOOD.

Interview with composer Michael J Lewis.

TO THINE OWN SELF BE TRUE.

JF: One of things I consider to be so fantastic about the score is how successfully the balancing act was achieved between a serious and dramatic musical approach and yet a sense of fun and irreverence, which perfectly complements the character of Edward Lionheart and Vincent Price’s portrayal of him.

I'd be interested in any thoughts of yours on how you came up with the material for Theatre of Blood, and how you may have decided on this approach.

MJL:

Without doubt, one of the reasons why the score compliments the movie so well was the relationship that developed between the director, Douglas Hickox and myself. Dougie was very intelligent, a well versed film-maker with a sharp sense of humour. A joy to work with. The concept for the film too was just great - thanks to the producers Stanley Mann and John Kohn and a great script by Anthony Greville-Bell. A good team working together with an absolutely magnificent cast. A walking who’s who of the London theatre, with Vincent Price and Coral Browne added for great measure.

What was my inspiration? A series of murders lifted right out of Shakespeare, which screamed for a classical approach. That was me. Drama, variety, fun.

Douglas had obviously listened to my earlier scores for 'The Madwoman of Chaillot,' (starring Katharine Hepburn) ‘Julius Caesar,' (starring Charlton Heston) and ‘Upon This Rock.' UTR was a dramatized documentary of St Peter’s Basilica in Rome starring Orson Welles, Ralph Richardson, Edith Evans and Dirk Bogarde. I regard this score as my best work and no one, lamentably, ever refers to it. Very sad. These three scores became our points of reference. We played tracks from each movie up against sections of T of B. It was a highly enjoyable exercise and we learnt a lot. We found out what worked and what didn’t work. We did our homework, we prepared well.

When the director and composer are completely in sync, with the backing of the producers, sparks can fly. Dougie encouraged me to allow the music to work in counterpoint with the action. We had learnt from our tests with earlier tracks of mine that the more dramatic, the more intense the music, the more effective it became. I was in my element. I love being uninhibited - slightly over the top. Unbridled passion.

Certain sequences were directly inspired by Dougie's love for cues from 'Upon This Rock' principally the Finale of T of B and The Trojan Trail, (Friends, Romans, Countrymen). There are also hints of ‘Julius Caesar' and ‘The Madwoman of Chaillot’ in the Ides of March. Full credit must be given to Douglas for the approach to Cymbeline (Edwina’s Theme). He thought that the bloody sawing off of Arthur Lowe’s head should have a touch of Dr Kildare (a popular medical series of the time starring Richard Chamberlain). It was a stunningly good idea that I totally applauded and went along with. A romantic theme played on piano and lush strings, which became increasingly ardent while blood spurted and poor Arthur’s head rolled off the operating table down onto the floor. This was music in direct counterpoint to the action, making it wickedly funny rather than grotesquely obscene. I am so proud of this sequence.

Another sequence I am very proud of is "I'm so glad you've come." Diana Dors and Jack Hawkins at their deceitfully lustful best. A touch of French, then a little light jazz, ending with pure German Wagnerian melodrama. What more could one ask for? "Sexy lips and swinging hips!” - another totally tongue in cheek track that gets a lot of attention. A fitting tribute to Dame Diana Rigg. Flugelhorn solo by late, great Stan Roderick.

A film for the ages with courageous film makers who realized that the wisest thing to do was to select the best talent and then get out of the way and let them get on with it - without interference. Being in England, far away from the California studios made a huge difference. Totally different worlds.

All too soon, the digital era, with ever-increasing quality samples, crashed the party, allowing producers, directors, writers, secretaries, executives, coffee maids to cast judgment on a score before the recording sessions were even booked. Ever more realistic 'mock-ups' were called for that ‘they’ could then pick apart in an attempt to prove their cleverness, justify their salaries and cast judgment over a beleaguered composer who had to expose his work before he/she ever got to the studio and the inspired musicians waiting to add their magic to his/hers music. The more ‘they’ picked, the more ‘they’ diluted the score to the detriment of film music. Overnight the maestro went from being King to humble servant and everything started to sound the same. The wonder of turning up at a session with a huge pile of manuscript paper for the musicians and hearing the score burst into glorious being for the very first time, uncensored and unmolested, was tragically over. Music needs musicians, live highly trained musicians with beating hearts not technological computer chips.

A few years ago, I was hired to score a really spectacular documentary. It was a terrific piece of film making. Abbey Road was to be the recording venue. Big name London orchestra. As I composed, I told the producers how enthusiastic I was about the project and that they should just sit back and patiently wait for the wonders to come. The score was going to be as spectacular as the images. Over the weeks, the more excited I became, the more suspicious they became. They just didn’t get my passion. One day the inevitable happened. The producers told me that they had hired a music supervisor (with no major movie experience) to check me out and that I had to produce a 'synth' mock-up of the entire score before we went to London to record. Without hesitation I refused. I would never have signed a contract agreeing to that. The whole process would have completely ruined the flow of my composition. They fired me and denied me payment. I threatened to take them to court and make them pay for my work. They paid. Meanwhile they hired another composer, who presumably wrote just what ‘they’ wanted under the eagled-eyed scrutiny of their interfering music supervisor.

The film, which was very good, actually got an Academy nomination but failed to get the Oscar. I found the courage to watch the scored film. The filming was still spectacular, the score unbelievably inert. Passionless, devoid of any energy. The vultures had done a great job.

Can you imagine Stravinsky doing a demo of ‘Firebird' and offering it to his critics before the first performance? The masterpiece would never have been heard. Stravinsky trusted his own creativity, got performed, booed, hissed, ridiculed and then a century later ended up with a 'pop' classic of outstanding originality.

You may or may not know that ‘they’ wanted to throw out ‘Moon River’, one of the most outstanding songs of all time by Henry Mancini and Johnny Mercer, from ‘Breakfast at Tiffany’s’. Audrey Hepburn saved the day by refusing to do any promotion for the film if the song was removed. Thank God ‘they’ lost.

JF : Was there an emotional sense in you that you responded to and tried to convey in the score?

MJL:

All my music is purely spontaneous and inspired by the film. The movie is my mistress, it tells me exactly what to do and I never argue. I always listen and do just what I am told. I don't have the intellect to do otherwise. The 'silent' opening title of T of B dictated to me the direction to take. The mandolin (chosen over the harpsichord) has great poignancy as does the flute. G minor has great drama e.g Haydn 39, Mozart 40, Shostakovich 11 (all late, mature works). The opening title became 'The Overture to Theatre of Blood.' It set the mood for the drama to come. Once I got the emotion of the opening theme, everything else flowed. The Welsh (I was born and raised in Aberystwyth, Ceredigion) love their minor keys, you know - they are so much more emotional than their major counterparts. One of the first pieces of music I fell in love with was Joseph Parry’s great E minor hymn tune, Aberystwyth, written while he was Professor of Music at Aberystwyth University – in fact the very first professor. A mighty tune, which captures, in a mere 16 bars, the passion of the Welsh, living a life of drama on the shores of the unpredictable Atlantic Ocean, at times sublimely calm, at times ridiculously wild.

JF : One of the aspects of the film that I think works particularly well is the fact that Edward Lionheart really is committing a lot of evil and grotesque crimes, and yet somehow still manages to be the protagonist. Ian Hendry as Peregrine Devlin is really the one who should have the sympathies of the audience and yet there is something tragic about Lionheart’s death at the end, even though this allows Devlin to survive.

I think the music greatly contributes to this, and that we got this right from the effective opening of the film. It gives us something about the motivations behind the Lionheart’s, that they’ve got pure and artistic ideals at heart.

MJL :

Lionheart had such a presence that Devlin could never really compete. The actor had justice on his side - a dedicated, uncompromising artist seeking revenge for being undervalued and denied the respect and adulation he deserved. Potent stuff. Love it.

T of B is not a 'horror flick' or 'a monster movie'- it’s a bone fide black comedy with a legit classical background.

Film music is in essence incidental music, be it Mendelssohn's 'Midsummer Night’s Dream,’ Prokofiev’s ‘The Queen of Spades’ or Jarre’s incomparable ‘Lawrence of Arabia.’

The essential task of a good score is to be subservient, to compliment the film. But in no way does this mean that the score has to be forgettable. Nothing is more memorable than a good tune. Having a good melody at the beginning and a good emotional melody at the end helps enormously. As the old proverb says. “A good beginning maketh a good end.”

JF: Even though there’s a lot of expressionist acting and action throughout (and arguably the opening images of Shakespeare from the silent era could work with large exciting music over top), it really eases us gently into the film.

MJL :

Naturally. Look how we are 'eased' into Bruckner 4 and 'Petrushka.’ No need to give it all away at the beginning. There are two hours to go. Plenty of time to climax. I never ever considered a ‘large’ sound for the opening for T of B. My original instinct was poignancy. That’s what my mistress told me. I listened. I did what I was told and over forty years later people are still talking about it. - J

JF : I wonder if it’s the amount of gentleness expressed here with only the mandolin and flute tentatively delivering the first tentative statement of melody that almost subconsciously aligns one’s sympathies with the actor, rather than the critic, and if you had any conscious ideas of this when you were doing that (see Main Title, below).

MJL:

I have no conscious idea of what I do. As I said earlier, I listen to my mistress, intently. There is no time to think in film scoring. (60 minutes of music in 5 weeks!) I composed and orchestrated every note for ‘Sphinx.’ No time to think, just do. Frank Schaffner told me after the recordings that “no one could have done the score better.” Considering his pedigree, I felt very proud of myself.

I hear a lot of scores today that are very clever, very well thought out but, to me, emotionally barren. McCartney claims that he woke up with a completed "Yesterday” in his head. He never thought about it until it simply appeared. A great, great song spontaneously conceived without any thought. Very nice.

Jazz players turn up to a gig, have a few beers and a laugh, sit down on a stool and play. Louis, Miles Davis, Dave Brubeck, John Coltraine. Natural. Spontaneous. It’s like sight reading versus practice. I have known great players who can play a concerto with great style, given enough months to practice, but were unable to sight read the simplest hymn tune.

JF : At the end of the film even though it seems the success of Lionheart’s master plans appears to not be possible, there is definitely something heroic about how you underscore his actions, something that suggests that the audience is to be on his side

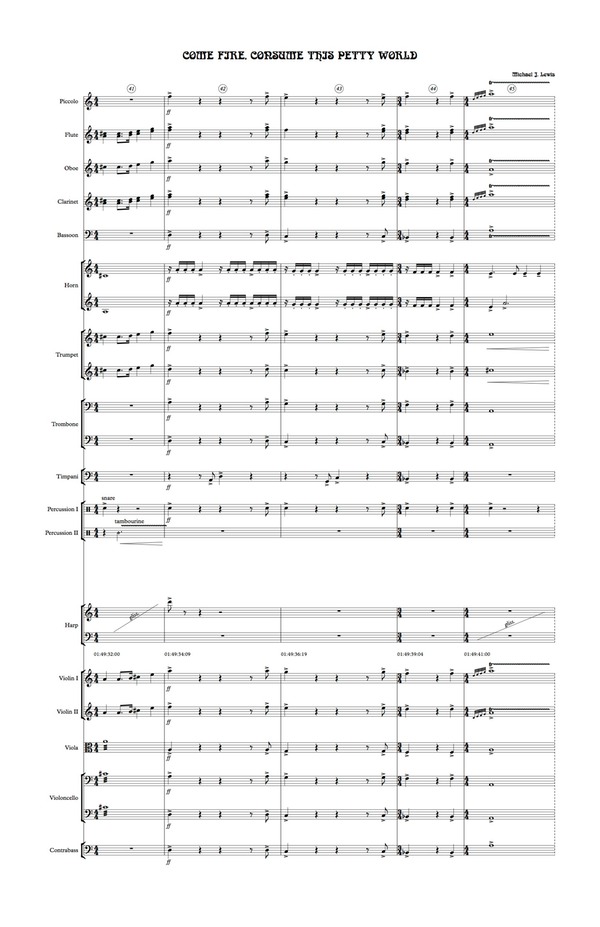

(See "Come Fire, Consume This Petty World", below).

Did you see that character like this?

MJL:

There is something heroic about all actors, writers, composers, dancers, painters who believe in themselves, but are frequently ignored by the world. Yet, they battle on creating because they have to, want to, need to. Good or bad, Lionheart was a true actor. He loved what he did but was denied the ultimate prize. Unfortunately he had to pay for his excesses – as we all do.

JF : This sense of serious playfulness extends to how you treat the melody throughout the film. Much like the characters within are all actors, the melody appears in different guises throughout, from the main title to ‘master of the killing phrase’, ‘to be or not to be’, ‘partita of blood’ and the end titles. Each has a different treatment (costume), from a sort of mediaeval arrangement to the most-contemporary sounding end title.

This sense of playfulness even extends to you varying the key each time it enters (from Gm to Em for ‘Fear No More’, Am for ‘To Be’, Dm for the ‘Partita’ and finally Fm for the end title). Was it important that you have a central melody to build the score around, because there are lots of other cues that do express a purely emotional state in a less-thematic way and one sequence (‘Ides Of March’) that sounds almost improvisatory in its chaotic nature, and yet the main theme still seems to be at the heart of the score.

In addition to this, there are traditional forms being used in the score (such as the fugato under the swordfight) and contrapuntal writing throughout. The effect it creates is both exciting and unique (particularly in scenes like the swordfight).

Were these instinctive decisions?

MJL:

Yes. But to me they were very obvious decisions. What form other than a fugato would you possibly use for two guys chasing themselves about on a pair of bouncing trampolines? It was a natural. I just looked at the scene, a great scene, and the scene told me what to do. The only choice left was the tempo. So I looked at the scene a second time and it dictated the tempo. Malcolm Cooke did a fine job editing the film. He got the tempo right. Who was I to argue?

Most of the early film composing greats, Miklos Rozsa, Max Steiner, Dimitri Tiomkin, et al, who arrived in Hollywood were Europeans with strong classical, symphonic background. Sonata form was in their blood. Thematic development was essential, it was designed to hold the audience emotionally and intellectually. Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Brahms, Bruckner knew it well and so should we or has the quality of the digital sample become more important?

JF: Were there any opinions from the filmmakers as you were creating the music?

MJL:

As I said earlier, my best directors have always trusted me and left me alone. I have been blessed to work with great men, Bryan Forbes, Douglas Hickox, Franklin J Schaffner, Jack Gold to name a few who have trusted me, absolutely, and just left me alone to do what I do best, spontaneously and without question.

Maybe they would ring up once or twice to keep in touch and ask if I had everything I needed, if everything was OK. They were all very polite gentlemen. Sometimes I would play them the cue I was working on at that very moment down the phone. They would politely say "Great" but I knew, and they knew, that it didn’t make much sense to them – I am not a very good KB player. All they wanted was to hear the track up against the picture adding magic to their images. I did a lot of major commercials in New York for a director who used to tell the clients that my music made his little pictures look big. They paid me well.

I have never let down my directors and producers and have never lost a cue, let alone a score. In the sad case of the documentary ‘they’ never even heard my score. Neither did they win the big prize. Needless to say, in my humble opinion, had they exercised a little more trust we would all have a little more gold adorning our mantelpieces.

JF : Have you any memories of the recording process, such as: Choosing the musicians, because there are some unique aspects to the orchestra you use, such as the mandolin and keyboard instruments.

MJL:

I would tell my contractor, the late Sid Margo, what line-up I wanted and he would always come up with the best. Whatever, whoever I needed I got to perfection. Whether it was a tabla player, or a santoori player or a mandolin player or a Cor Anglais player, I always got the best. The better the instrumentalist the easier they are to work with and, of course, the more pleasurable. In all my years of recording, with the very best in the world, London, Berlin, New York, Los Angeles and recently Austin TX, only one muso failed to please - a second rate guitar player in London years ago who slipped through the net on a too busy day and was never called again. Ever. I have a harp player in New York who always gets to the sessions 40 minutes early and the first thing she says to me is "anything you want Michael, anything you want." She always delivers and always gets the gig.

JF : Did you choose any players personally, were these musicians you were used to working with at the time?

MJL:

When I meet an outstanding player who understands me, with as few words as possible, I stick with him/her. I first worked with Hugo D'Alton (Mandolin) on ' ‘Madwoman.' Outstanding player. Very intense. Desperate to please.

We all need each other. We all need to be creative, spontaneously creative. I have tried to work with great players who cannot read. For me it just doesn’t work. It takes too many words to get started. I love meeting a player and we just groove from the start. When they get the message, I encourage them to go a little further, push them a bit. Good players love being pushed as long as they sense that you, the composer, know exactly what you want and that you know precisely what you are doing. Never give a fine player an unplayable part. You will have lost before the downbeat.

JF : Do you remember where it was recorded (there’s a bit of a CTS sound on the echo-y reverb but I’m no expert in these things)?

MJL:

T of B was one of the last scores to be recorded at the old CTS Studio in Bayswater, London. I started my recording career there with 'Madwoman.' All the great Hollywood cats would come over to record there. Great sounding room demolished to make way for a retail store. Happens all the time. I used to love working at ‘O Henry's' in Burbank, CA. Beautiful sounding room, now shut. CBS in New York, regarded by some as the greatest room of all time, long gone. Apartments now, I think.

It was at CTS with engineer John Richards (who recorded all the early Bonds with the masterful John Barry) that I learnt the delights of multi-track recording, which in a span of just a few years or so went from 4 track (one reserved for sync) to 1 inch 8 track to 2 inch 16 track and then bliss upon bliss 24 track – even 48 track if you coupled two 24 track recorders. Heaven. It was at CTS that I learnt all about mixing and faders and reverbs, plates, chambers etc. Reverb was very much an English thing at that time. California caught up later. Nothing ‘echo-y’ about judicious use of reverb. Sonic enhancement is nearer the mark!

I have loved the studio life from Day One. Great engineers, in great rooms worldwide. At the moment I work at a studio in one of world’s most exciting cities – New Orleans – home of Louis, jazz and jambalaya.

Over the years, I have seen huge technological changes. Tape came and went as did cassettes, cartridges and CDs. Hard drives became smaller and smaller until now, when you can put a thumb drive in your pocket. I have never involved myself in the hardware side of things (I know too many outstanding engineers) but I have always kept up with the advances in technology. Essential.

JF: You’ve written orchestral scores as well as more pop music oriented scores (such as the main title for ‘The Man Who Haunted Himself’ or much of ‘92 In The Shade’) and a considerable amount of music outside the film and television genre.

Is there a common approach when first approaching a piece of music whether it’s for a film or say, a choral piece, or do different genres get approached in different ways?

MJL:

The only approach I know is to be excited by the challenge of writing and recording a new work no matter the genre. The driving force for any creator is the simple question that haunts us all every morning. Can I write today as well, or better, than I did yesterday? I also believe that you have to be dedicated to writing for posterity and not prosperity, which can mean being unflinchingly uncompromising at times – very difficult in the film world. If a note is wrong it’s wrong. If it’s going to cost $$$$ to change it then $$$$$$$$ have to be spent. If you compromise today, you will pay for it tomorrow for sure. Once a recording is released, you can never recall it. Once you press send, it belongs to the world. I have to enjoy and believe in what I am doing. I relish variety. I thrive on writing in a style I have not explored before. I recently completed a 17 minute track for full classical (sampled) orchestra elevated by live alto sax, country harmonica, electric guitar, 6 string electric bass, vibes, jazz piano and multiple ethnic percussion all playing from a basic topline. No written score. We maxed out Pro-Tools at 96 tracks. The piece grew spontaneously each session. The end was unknown until we got there. I played all the orchestral parts. Great soloists in Austin did the rest. Great musicians bring greatness to your work. Thank God I never had to consult a director or a producer or any of their minions. It’s my project. A 17 minute story told through modern dance that is still seeking an ‘angel’ – a very wealthy ‘angel.’

"The Man Who Haunted Himself" was my first excursion into the 'pop world’ type score. I got an arranger to write out the drum, rhythm guitar and electric bass parts. They looked wildly complicated and were wildly complicated. When I got to the studio, the rhythm guys on the session took one look at the charts, choked, asked me what the hell was this s..., and suggested I tore up the parts (which I immediately did). They then proceeded to play something many times better. Ever since that time, the only part I have ever given a rhythm player is a bar chart and chord symbols. Working with rhythm players is always wildly creative, hugely fun, highly satisfying, totally spontaneous.

I am now working on a programme of a cappella nineteenth century art songs. Never a dull moment.

Thanks for mentioning ‘92 in the Shade’ – another minor key tune. The track on my Double CD ‘The Film Music of Michael J Lewis’ was an arrangement for harmonica and steel string guitar I wrote for the album. Two of the best musicians I have ever had the pleasure of working with – Tommy Morgan (harmonica), Carl Verheyen (guitar) came into a little garage studio in North Hollywood. I gave them the topline and explained as briefly as possible what I wanted. They gave me what I asked for in one take. Stunning cooperation and understanding between musicians and composer. I was my own producer. I financed the entire project. Since the Double CD recording, I have continued to work on the original track, because I love it so much, adding pedal steel, fretless bass and real strings. No synths, nothing digital other than good old Protools and, of course, outstanding, live musicians. The final arrangement can be heard on my guitar CD ‘Incandescence.’

I have just seen a very interesting trailer for a Hollywood movie to be released this fall. The director is also the writer, lead actor and producer. He stuck with the project for years until he finally got it made. Resolute persistence. Unwavering conviction. The soundtrack is big band from the mid-twentieth century, the period in which the movie is set. Music from the pre-digital era. Great stuff. I pray that the feature gets solid reviews and finds a big audience. We need more auteurs who can exercise strict control over their work and resist the interference of them who know not what they do.

Theatre of Blood also had a creative team who believed in their project and in each other, who supported each other. They, led by Douglas Hickox (who passed away far, far, far too early), encouraged me to be courageous, to cast aside the norm and be adventurous, spontaneous, fearless, to have fun. Failure never entered our heads.

In the arrogance of my early days I had initially turned down the film – can you believe it? It had been pitched as a horror flick, which honestly did not appeal to me – it reeked of Hammer Films (Britain’s leading horror factory of the time out at Elstree.) However, the producers were persistent, resolute, unwavering. The second time, they pitched the film as a black comedy based on Shakespeare. I went, I saw and was conquered. I am so grateful to John, Stanley and Douglas who taught me to ‘fear no more the heat of the sun’ and in doing so gave me one of the most enjoyable, and creative experiences of my entire career. Originally titled ‘Much Ado about Murder,’ Theatre of Blood is still ‘Alive in Triumph.’ Thanks guys. ‘Thou, thy worldly task hath done.’ ‘To thine own self be true.’

Michael J Lewis

Huckleberry Place, Mississippi.

September 1 2016

© 2016 Michael J Lewis